Jan 26, 2026

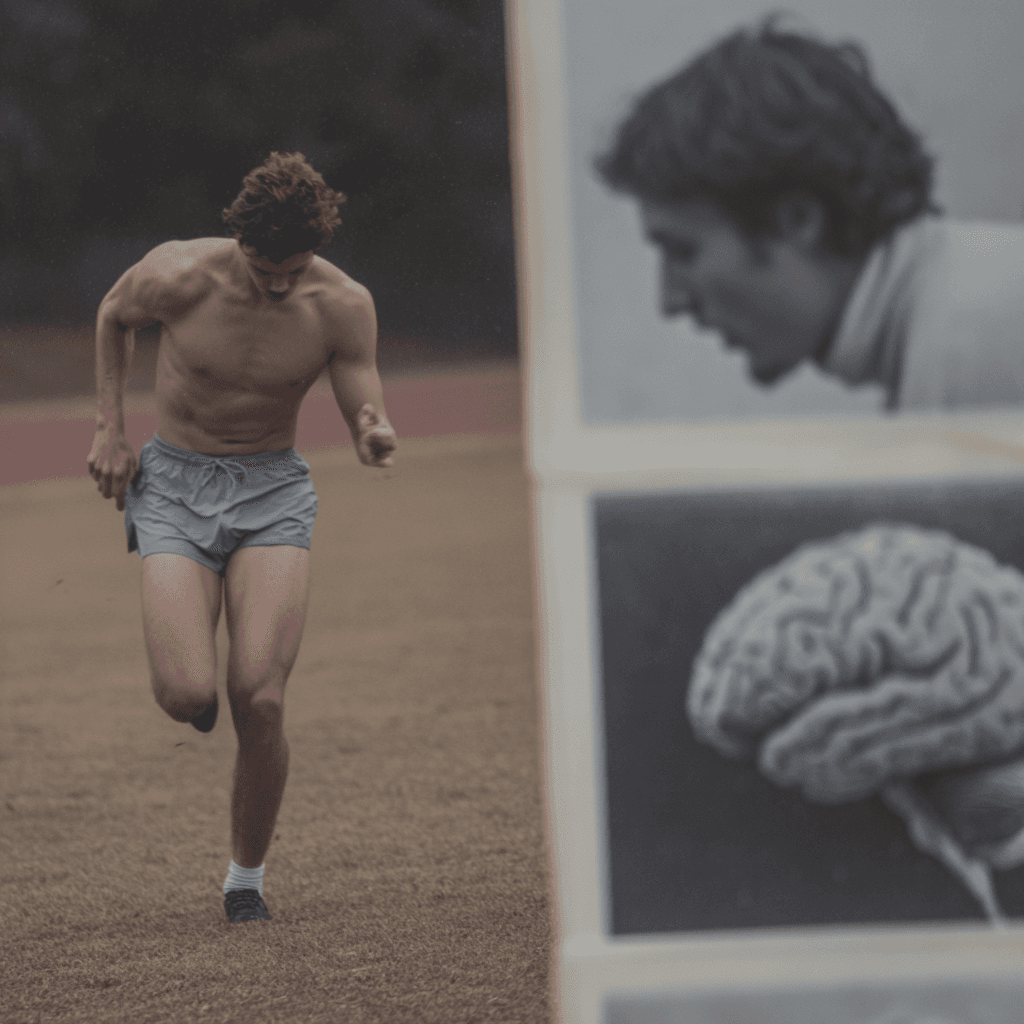

How to Become A Movement Genius

Your Shortcut to Moving Freely Again

Still struggling with stubborn knees, back, or shoulder pain? Get a personalised program that works when nothing else has.

How To Become A Movement Genius

I’ve learned a lot of different skills in my life and with each one, I got faster at learning the next; even when they had nothing to do with each other.

My goal with this ebook is to help you rapidly accelerate your skill learning journey. To give you the tools, strategies, and mindset to compress a year’s worth of progress into a single month.

Thinking Patterns For Skill Acquisition

Spiral Growth

Spiral growth means every skill you learn builds momentum mentally and physically for the next one. You learn faster because your brain recognizes the pattern, not just the movement.

The reason you can become such an athletic freak with this method is because all skills are learned in a pattern. Repeating that pattern makes it more and more ingrained in your head, so it happens subconsciously.

When learning a backflip, fear coursed through my blood. Now I can send it whenever. A month after the backflip, I learned a back full on the trampoline (a backflip with a 360), and my brain had the exact same feeling as when I first learned the backflip except I knew how to deal with the “fear” emotion this time.

Care Less

Performance will always become less optimal when you dwell on past mistakes. If you're stuck thinking about the last rep, you're more likely to repeat it. You need to care less.

No rep is good and no rep is bad. They’re all just a way to take in external noise and translate it to learning.

It’s normal to feel like you’re “messing up” more when training this way. But here’s the secret: worse performance (as seen by traditional training) in the short term often leads to better learning over the long term. Differential learning has shown again and again that retention and adaptability improve way more than if you just drill something to perfection.

Ironically, caring less about perfect results often leads to better results. Because you’re not locked up in your head you’re adapting.

Play More

Your play type; the way you naturally engage with challenge is another key to unlocking faster learning.Everyone plays differently and how you play affects how you learn. When you tap into your natural play type, skill development becomes effortless, fun, and fast.

Remember this: when we smile, we learn faster.

This idea is backed by a study from Kareem Johnson (Temple University), which found that people exposed to happy faces improved performance on attention-related tasks. Your emotional state directly impacts how fast you learn. So if you’re not having fun, that might be the real reason things haven’t clicked before.

This section will help you fix that, so you can actually enjoy becoming a movement genius.

(You may need to think back to how you played as a kid to figure out which one you truly connect with.)

The Joker

Plays with humor and silliness. If others are laughing, they’re enjoying it more. When learning, it’s crucial for these people to be silly and joke around. If not, learning drags and probably won’t sink in.

The Kinesthete

Loves to move. These are the kids who wrestled, jumped, and stayed active. Sitting still or watching TV doesn’t excite them. Moving is where they is what they enjoy the most.

The Explorer

Chases novelty. Anything new physically, emotionally, or intellectually is fun. They often find differential learning super engaging because it’s always changing.

The Competitor

Keeps score. Wants to win. Will even slightly adjust the rules to do it. This play type often stalls out if they think they’re already the best. Learning is boring unless it’s to win.

The Director

Wants to coach more than play. They learn the most by teaching others. Learning for them is often about gaining mastery and authority.

The Collector

Probably has some sort of massive collection at home. If they see skills as things to collect, they become unstoppable learners.

The Artist/Creator

Lives in the world of building and DIY. If you’ve ever spent all day creating something and lost track of time, this is likely you. Skill learning becomes art when you see your body as clay to shape.

The Storyteller

In it for the journey. They love books, theater, and watching stories unfold. Creating a personal story around your movement journey is key for this type.

Once you know your play type, design your practice to match it. Don’t fight your style—use it. The more fun it feels, the faster you’ll grow.

The #1 Concept That Changes Everything: Differential Learning

Humans learn from difference. Too much difference, and our brain gets overloaded. Not enough, and the brain shuts down from boredom.

Difference is often referred to as noise. When you find the right amount of noise, it stimulates the brain to adapt. That’s where the magic happens. That’s how you unlock the movement genius you haven’t fully tapped into yet.

The 4 Pillars of Differential Learning

(1) Why Should You Use Abundant Variability

Humans learn through difference. It’s how we learned to walk and talk as kids. We didn’t just repeat one perfect rep; instead we played, failed, stumbled, tried again, and our brains made sense of it through all that variability.

Somehow we lose that way of learning as we get older. But we can go back to it.

Fear is usually the biggest limiter, which is why we start slow. The cool part is this kind of learning taps into the same system you used as a kid. Novel movement triggers neuroplasticity—your brain’s ability to rewire and adapt. You’re training like a child again, which helps skills lock in for life.

The benefit is massive. Imagine learning something once, then never losing it. Think about it. Have you ever woken up and forgotten how to walk? Probably not. Even after comas, most people can still walk. Why? Because it was learned through noise.

A study by Tassignon et al. (2021) showed that skills learned through differential learning are more deeply ingrained in the nervous system. That means you can take a break, come back, and pick the skill up again in seconds.

(2) How to Leverage the Body’s Natural Desire to Learn

There’s a concept in physics and biology called stochastic resonance; a weak signal becomes more noticeable when a certain amount of random noise is added.

Same thing happens in your body. When you train with variation, your nervous system has to filter through it and self-organize. That’s how it finds the most stable solution.

Santos et al. (2018) found that soccer players using differential learning didn’t just learn skills faster, they became more creative and made better decisions during games.

This shows us that the body doesn’t just learn through noise, it thrives in it. That’s what separates average athletes from exceptional ones.

(3) Are You Always Behind? Find Your Unique Technique

There is no perfect technique.

We all move differently. Our biomechanics are different. Our injuries are different. So the brain has to figure out your version of the technique, not someone else’s.

Differential training helps with that.

Henz & Schöllhorn (2016) found that this method not only improves learning, but lights up the brain more deeply. EEG scans showed increases in theta and alpha brain waves, which these are tied to memory consolidation and sensorimotor integration.

That’s how you create your version of the skill. Your blueprint.

(4) Repetition With Instruction Is Killing Your Results

The biggest killer of learning? Boredom.

The brain doesn’t get tired. It just checks out when it loses stimulation.

In differential learning, that doesn’t happen. You’re constantly adjusting, adapting, solving new movement puzzles. You stay locked in.

Apidogo et al. (2022) found that learning multiple skills at once using differential learning can actually be more effective than drilling just one. More variety = more results. And faster.

Application/ How To Use Differential Learning

During a differential session, each rep should change slightly. These micro-variations keep the system engaged and learning. The bigger the change, the harder the challenge.

Below is my best attempt to organize all of the differences I have seen used in Schöllhorns’ work and what I have tested myself.

If you’re brand new to this, pick one variable at a time. Add more as you get comfortable. Eventually, you’ll be mixing multiple internal and external variables without even thinking about it.

EXTERNAL: Environment and Equipment

The environment involves game-like changes. Simply playing a sport already builds some environmental adaptation, but when these variables are specifically altered, it can create monumental results.

Ground and Field:

Play on dirt, grass, or turf

Switch between indoor and outdoor surfaces

Try bumpy vs smooth terrain

Other Players:

2 vs 1 in tennis

Add or remove defenders in drills

Increase unpredictability by changing team size or spacing

Contrast / Chaos to Calm:

Throw balls across the court or field to dodge during play

Train with loud, distracting music, then switch to total silence

Equipment means the actual tools you're using—and how they affect movement. Changing the tools forces the body to adapt to new feedback. This is often very sport-specific but works across the board.

Weighted:

Use men’s vs women’s basketballs

Golf with heavier or lighter clubs

Longer / Shorter:

Vary shot distances in basketball

Use different club or bat lengths

‘Wrong’ or Odd Equipment:

Use a stick bat in baseball

Try juggling a shoe instead of a soccer ball

The more contrast you build in, the more adaptable your nervous system becomes. It learns to solve problems under different conditions, which means when you're back in normal conditions, performance feels easier.

INTERNAL: Body Position and Mental Focus

This is where you get to be creative.

Body position has endless variations. You can break it down so far that even flexing a different finger on each rep becomes part of the learning. Here are some of the most common variations:

Stance / Legs:

Wide, narrow, single leg, staggered, crossed

Arms:

One arm only

Arms behind back

Arms overhead

Torso:

Leaning forward

Side bends

Arching back

Eyes:

One closed, both closed, blinking pattern

Head:

Looking up, down, left, right

Side-to-side movements

To level it up, increase dynamic movement with a body part during the rep. One of the hardest? Head movement. For example, rapidly turning your head back and forth while dribbling. That’ll light up your system fast.

Mental Focus

Mental focus is the most complex (and underrated) form of noise. This is what creates the feeling of your brain being pulled apart and forced to function at a higher level.

Examples:

Muscle Contraction Cues:

Flex the left glute during a left-handed macaco

Isolate and contract specific muscles as you move

Math Problems (Coach Says):

“2+2”

“Square root of 144”

“2+5–4x1”

Sing a Song:

Karaoke style

With or without music

Memorized Patterns:

Recite the ABCs

Use call and response

Speak memorized lines mid-rep

Out loud is best, but even doing these in your head creates solid noise.

Example Sessions

Here are two example lists to help spark ideas.

Soccer: Coaching Cues

Approach from a wide angle

Approach from a narrow angle

Plant leg behind or in front of the ball

Use your toe

High loft shot

Low drive

One-step run-up

Five-step run-up

Close left eye

Close right eye

Throw a tennis ball before kicking

Flex calf of kicking leg

Flex toes of support leg

Arms above head

Arms behind back

Slow approach to kick: 10 seconds (3 steps)

Fast Approach: 2 seconds (3 steps)

Tennis: Coaching Cues

Alternate grip types: Eastern, Western, or “wrong”

Step forward or backward on contact

Bend knees super low

Stay tall

Swing early or late

Lift racquet high before swinging

Jump while hitting

Hit two balls at once (coach to player)

Look left while hitting to the right

Look up for entire hit

Move head right while hitting to the left

Play loud, explicit music

Switch to Mozart

Flex wrist before swing

Think of opposite glute contraction (right-hand = left glute)

These are just starting points. You’ll come up with more as you train. Once you get used to building noise into your reps, it becomes second nature.

Important Notes For Coaches:

There’s no right or wrong form of noise

Let the athlete learn through self-discovery

Your job as a coach is to guide, not dictate

Too much noise all at once can kill motivation

Learning Systems I Use Daily

All of these methods are based on differential learning. That’s why they work.

I didn’t learn them from a textbook. I discovered them, some from instructors and others from the pure desire to learn faster and more efficiently. I’ll give you the background on how I started using the methods, how they helped me, and where they can go sideways if you’re not careful.

1. Funnel Method

This one’s about using overcorrections to narrow in on the idealized outcome.

If I’m too slow, I aim to be too fast on the next rep. Miss left? I’ll aim to miss right next time. The point isn’t perfection—it’s to build boundaries so you can zero in on the center. Over time, those extremes “funnel” into accuracy.

Benefits:

Wildly fast results. I’ve seen beginners dial in passes with incredible precision in just one session.

Great for skills with no risk of injury.

Caution:

This method has real risks. When I was learning 360s snowboarding, I kept under-rotating. So I told myself to overspin. That worked—until I landed on ice, overspun, and broke my clavicle. Not fun. I suggest you use this method on low-risk skills only.

Where I Found It:

This came out of my time learning to play tennis and soccer. I found if I tried to make minor changes nothing would happen but if I made major changes my body began to adapt. Because if this is I overshot, I’d aim to undershoot the next rep. Coaches weren’t also fans of this in game, but I improved and began hitting shots and angles that were out of my league.

2. Imagine Method

This might be the most underrated.

Why? Because there’s no physical risk, but huge mental reward.

You convince your subconscious that you already know the movement. You imagine it fully; start to finish. The key is you can’t stop halfway. Visualizing half a backflip teaches your brain... how to do half a backflip. That’s not helpful.

Best time to do this? Right before bed.

And it’s not woo-woo. Richardson’s 1960s free-throw study found this:

Practice only: ~24% improvement

Visualization only: ~23% improvement

No practice: 0%

More recently, JEPonline (2023) confirmed that visualization plus practice beats either one alone.

Where I Found It:

This started in drumline. I’d mess up my marching patterns, so my instructor told me: “Think through your dots every night. Visualize each move.” I did—and never missed a cue again.

Later, in snowboarding, I used this to finally land the 360 and learn to ride rails. Before every attempt, I’d close my eyes and feel the movement. Picture it. Then send it. I still do this daily for tough stuff; flips, 5-ball juggling, anything complex.

3. Tempo Method

You take a skill and slow it way down. Like, snail pace. Then you layer in noise at that pace. That gives your brain time to actually process the movement and absorb feedback without getting overwhelmed.

Later, you flip it. Go super fast. Exaggerate the speed to be ‘too’ fast. When you return to a normal tempo, it’ll feel easier because now the pattern is slow for your brain.

Where I Found It:

Back in jazz band, I’d slow down complex drum fills, then blast them fast. That created the contrast I needed. I realized it works beyond music when I was learning to juggle. I practiced juggling slowly with 1–2 balls, then super fast. By the time I added a third ball, it felt simple because I already lived at both extremes.

What This Means Beyond Sports

Differential learning isn’t just about flashy tricks or game-day performance. It’s how you build a body and brain that can adapt to anything.

This system helps you do a back flip... but it also helps you hike rocky trails, lift groceries, and feel sharp every day. It’s movement intelligence that stays with you.

Final Takeaways

I hope this shows you that differential learning isn’t random. It’s noise with a purpose. You can tune that noise like music to create precision.

It doesn’t matter if your goal is a skill or a daily task, this system will get you there. And if you ever get stuck, just zoom out. Laugh a little. Change the noise.

Then start again. Smiling and laughing because we are learning like kids again. Fast.

You’ve got the recipe now.

You’re ready to become a movement genius.

Sources

Schöllhorn, W. I., Beckmann, H., & Davids, K. (2010). Differential training as a key innovation in motor learning – a commentary. Physical Therapy in Sport, 11(2), 46–50.

Schöllhorn, W. I., Mayer-Kress, G., Newell, K. M., & Michelbrink, M. (2009). Time scales of adaptive behavior and motor learning in the presence of stochastic perturbations. Human Movement Science, 28(3), 319–333.

Tassignon, B., Verschueren, J., Pans, L., Lenoir, M., & Deconinck, F. J. A. (2021). Motor learning through differential learning: A review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 51(9), 1897–1916.

Santos, S., Memmert, D., Sampaio, J., & Leite, N. (2016). The spawns of creative behavior in team sports: A creativity developmental framework. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1282.

Henz, D., & Schöllhorn, W. I. (2016). EEG brain dynamics during different types of motor learning. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10, 150.

Apidogo, A. A., Popp, J., & Schöllhorn, W. I. (2022). Differential learning improves the learning of multiple sports techniques simultaneously. Human Movement Science, 84, 102983.

Richardson, A. (1967). Mental practice: A review and discussion. Research Quarterly. American Association for Health, Physical Education and Recreation, 38(1), 95–107.

de Freitas, J. V., da Silva, S. F., & Lima, R. F. (2023). Mental imagery training in sports: A systematic review. Journal of Exercise Physiology Online, 26(1), 100–117.

Johnson, K. J., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2005). “We All Look the Same to Me”: Positive Emotions Eliminate the Own-Race Bias in Face Recognition. Psychological Science, 16(11), 875–881.

Brown, Stuart L., & Vaughan, Christopher C. (2009). Play: How It Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the Soul. Avery.

Waitzkin, Joshua. (2007). The Art of Learning: An Inner Journey to Optimal Performance. Free Press.

Gallwey, W. Timothy. (1974). The Inner Game of Tennis: The Classic Guide to the Mental Side of Peak Performance. Random House.